By: Regan Burke

The Community

The Jizo-an Zen Community is nestled in the heart of Cherry Hill, New Jersey. Only a block from Route 70, Cherry Hill’s main road, the Community is very accessible to residents of the town. Previously known as the Pine Wind Monastic Community, the Community was established in Riverton, New Jersey, then moved to Cinnaminson, New Jersey, before finally settling in Cherry Hill.

Buddhists comprise less than 1% of the population of New Jersey, which equates to less than 90,000 individuals. The Buddhist population of Camden County (the county in which Jizo-an resides) is slightly more dense, with approximately 9,300 Mahayana Buddhists. This figure equates to roughly 1.7% of the county’s population. In other words, Buddhism is far from a prevalent religion in that area. Because of their small size, the population of Buddhists that belong to the Jizo-an Zen Community is tight-knit and dedicated to their community, especially the dedicated students who volunteer their time to the betterment of the Community.

The Founder

Seijaku Roshi, the founder of the Jizo-an Zen Community, had an impressive career as a Zen master. He began teaching in 1975 following “a series of personal transformative insights,” according to the Community’s website. Ten years later, he founded The Zen Society, a nonprofit organization dedicated to a “mindful awareness of the needs of my body, my mind, my heart and other beings including the whole of nature,” as stated on their blog. On March 27th, 1993, Seijaku Roshi was installed as Abbot of the Jizo-an Monastery and given the title of Roshi during a formal ceremony. The Community emphasizes that this period marked a turning point in the regional Buddhist landscape, as his leadership helped introduce Zen practice to individuals who had never encountered it before.

The purpose of your your life is clear, to live it at the level of excellence and full self-expression and as a benefit for others. This is Nirvana, this is Enlightenment. — Seijaku Roshi

Seijaku Roshi taught for over forty-five years, influencing the lives and spiritual journeys of countless individuals. He regularly spoke at high schools, universities, businesses, churches, synagogues, and even prison and veteran outreach programs. Former attendees of these programs often describe his presence as both grounding and disarming, noting that he blended humor, clarity, and directness in a way that made Zen philosophy accessible to people from all backgrounds. He also authored the book “Kokoro – The Heart Within” – Reflections on Zen Beyond Buddhism, a collection of his teachings and extension of his dedication to spreading the messages of the Buddha beyond Buddhism.

Seijaku Roshi passed away on June 19th, 2021, at the age of sixty-six. The Community continues to use his teachings.

The Tradition

The Community follows the Zen tradition, an extension of Mahayana Buddhism originating in China and ultimately spreading to other East Asian countries. The Community credits the Japanese tradition of Zen Buddhism as the primary influence for their practices. They also acknowledge the broader lineage of Zen, which has historically evolved as it encountered new cultures, allowing practitioners to adapt rituals and teachings without abandoning the founding principles of meditation and awareness.

As an ancient tradition in a modern society, the Community has had to adapt the teachings of Zen Buddhism to the culture of today’s America—a challenge that is hardly unique to this U.S. Buddhist community. In order to reconcile the old ways with the new, the Community has embraced modernity as a tool for accessibility and engagement. According to the “Life’s Values” page on the Community’s website, this “departure from strict monastic customs reflects a dialog between modern and monastic life.” Thus, they accept modern technologies as a conduit to spreading the teachings of the Buddha.

While the Community embraces technology when used for Buddhist practices, it calls upon its members to “recognize all persons, and all creation, as the free gift of Buddha-Nature, God, The Universe” in “a society plagued by hyper-individualism, consumerism, fear, and wealth-inequality.” The Community encourages its members to acknowledge and appreciate the “interconnectedness and interdependence” of life; the Community’s perspective on modern society also reflects this interconnectedness and interdependence. A monastery in today’s American cannot cultivate engagement without interacting with their members digitally, such as live-streaming events. For the Community, these digital tools are framed not as replacements for in-person practice, but as extensions of the zendo, allowing members to carry mindfulness into their homes and workplaces.

This integration reflects a growing movement among American Buddhist groups to embrace digital connection as part of their mission rather than as a compromise of traditional values. Many communities currently utilize modern technologies for its benefits to preserving and spreading the teachings of the Buddha. Three Dharma mentors weighing in on this subject for the East Horizon Magazine are in agreement that technology is beneficial to Buddhist teachings as “[s]cholars can use technology to digitize and preserve ancient Buddhist texts, artifacts, and artworks” and “[t]his technology could offer new insights and perspectives on Buddhist heritage,” say the Venerable Aggacitta and the Venerable Min Wei respectively. Their comments reflect a generational shift in Buddhist scholarship, where digital preservation has become essential for safeguarding fragile manuscripts and making them available to global audiences.

Despite these benefits, the Venerable Tenzin Tsepal cautions that for the use of technology in religious settings, “strong core ethical values are necessary guardrails to guide developers to ensure human rights.” He suggests that “[m]any of our problems today are due to lack of awareness of an ethical dimension to our actions and the effect our actions have on others.” Aggacitta proposes the antidote to Tsepal’s technological poison: observance of five Buddhist ethical principles. He encourages Buddhists to “emphasize compassion and the principle of nonharm. . . encourage mindfulness. . . respect individuals’ privacy. . . cultivate equanimity. . . [and] recognize the ecological impact of technology and make efforts to reduce waste.” Together, their perspectives illustrate a broader concern within contemporary Buddhism about how rapidly changing technologies influence attention, behavior, and community life.

The Membership

Upon founding the Community, Seijaku Roshi established a path to Lay Ordination, which recognizes the important contributions that laymen and laywomen make to the spreading of the dharma. In order for these individuals to be ordained, they must maintain active membership to the Community for at least two years and complete the precepts class offered by the Community. Upon their ordination, lay practitioners receive the precepts from the abbot of the Community in a formal Jukai ceremony. This ceremony is representative of the practitioner’s dedication to living a life in accordance with the Bodhisattva vows. The Community views these vows not as rigid rules but as living commitments that shape a practitioner’s conduct, attitudes, and service to others.

Formal students in the Community can also pursue the Path of Service, a path which is only available to students who have “demonstrated a genuine interest in giving back to the Jizo-an Zen Community.” Those who pursue the Path of Service will fulfill responsibilities such as ringing the temple bell, passing out sutra cards to guests, greeting guests, assisting the tenzo, sounding the gong, and even leading zazen and kinhin practices. In order to pursue the Path of Service, a student must have already received the precepts and have been an active member of the Community for at least three years. This emphasis on service highlights the Zen understanding that spiritual development is inseparable from communal responsibility.

To pursue the Path to Full Ordination at the Community, a student must have been an active member of the Community for at least four years and served at least two of those years as a “Lay-Monk.” According to the Community’s “Membership” page, the long, arduous nature of the Path to Full Ordination is intentional. “This graded approach allows students to find out through experience whether monastic life is right for them,” says their website. “[This] reveal[s] the difference between the reality of committing one’s life to the Buddhadharma and any romantic notions about Zen training and monastic life.” This gradual process mirrors traditional monastic training in Japan, where students often spend years testing their readiness for the discipline and the simplicity required of monastic life.

The Practices

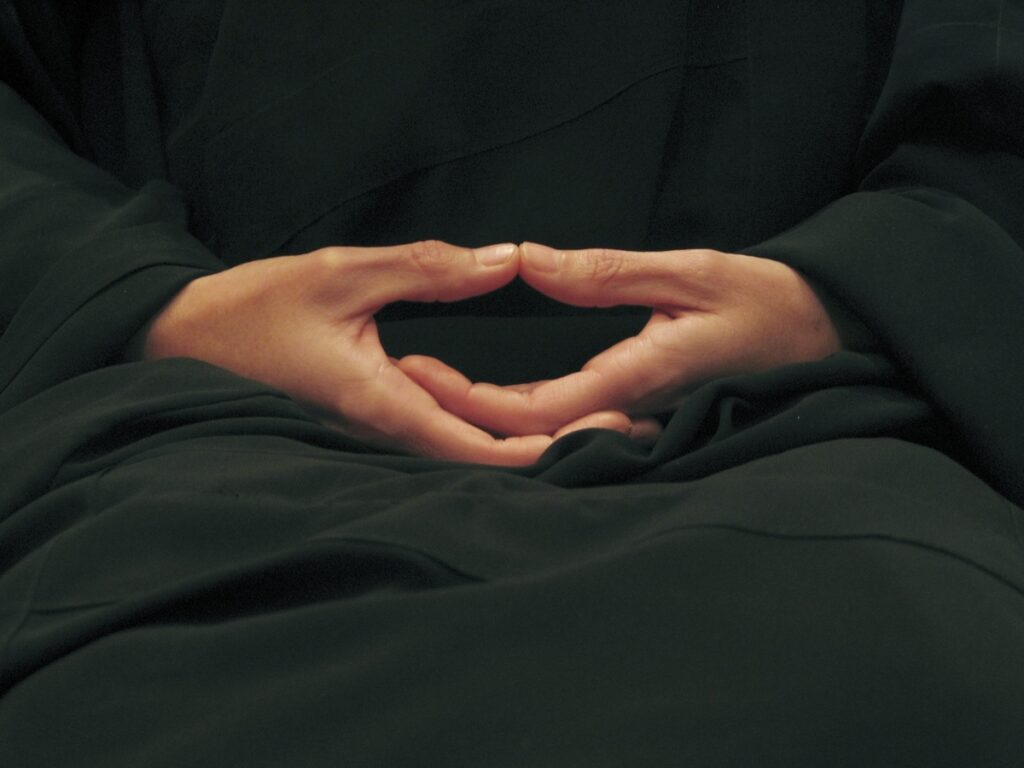

The Community places meditation and personal and community prayer at the center of community life. Each brother and sister’s day begins with reflective morning prayer. This morning prayer is live-streamed from the zendo to members at home. Throughout the day, members of the Community dedicate extended time to personal reflection and mindfulness. Members frequently describe these periods of quiet as essential moments for grounding themselves before transitioning into the demands of work, study, or family life.

Shared meditation, prayer, and educational opportunities are held at the monastery and online on the first, second, and third Wednesdays, Saturdays, and Sundays of each month. Wednesday evenings feature Zen Studies Programs. Recent Zen Studies Program events have included a ceremony in memory of the deceased and commemoration for those suffering in the hungry ghost realms and a discussion about the ever-changing nature of life through the metaphor of music. These events feature zazen, seated meditation, and kinhin, walking meditation. The combination of seated and walking practices is designed to help practitioners carry the stillness of zazen into movement, blurring the line between formal practice and the flow of everyday activity.

Funding

As a nonprofit organization, the Community’s leaders take no money from its members. Instead, these dues go towards the maintenance of the zendo and funding for the programs that the Community offers.

Jizo-an offers three levels of membership which vary in price. All memberships are granted unlimited access to online programs such as morning meditation. “Friends” of the Community are allowed one Wednesday evening Zen Studies Program at no extra cost, “Supporters” are given two Wednesday evening Zen Studies programs at no extra cost, and “Benefactors” are granted unlimited access to programs at no extra cost. Special programs are available to all members at a discounted rate.

Sources

Jizo-an Zen Community. Accessed November 30, 2025. https://www.jizo-an.org/.

“Clarence Reichenbach Obituary.” Mount Laurel Home for Funerals. Accessed November 30, 2025. https://www.mountlaurelfuneralhome.com/memorials/clarence-reichenbach/4647808/?proxy=original.

“Pine Wind Monastery The Zen Society.” Open Sangha Foundation. Accessed November 30, 2025. https://opensanghafoundation.org/newsite/user/pine+wind+monastery+the+zen+society/?profiletab=activity.

“Camden County, New Jersey – Congregational Membership Report.” The Association of Religion Data Archives. Published 2020. Accessed November 30, 2025. https://www.thearda.com/us-religion/census/congregational-membership?y=2020&t=0&c=34007.

“Buddhist ethics in the age of technology.” East Horizon Magazine. Young Buddhist Association of Malaysia, December 31, 2023, Accessed November 30, 2025. https://thubtenchodron.org/2023/12/technology-buddhist-ethics/.